Contesting a will in BC can be an emotional and complex process. If you feel you were unfairly left out of a loved one’s will or not adequately provided for, you do have options under British Columbia law. This guide explains in plain language how to contest a will in BC, including who can contest, the legal grounds, how long you have, the average cost to contest a will, and the step-by-step process.

We’ll also answer common questions (FAQ) to help you understand your rights under BC’s Wills, Estates and Succession Act (often still called the Wills Variation Act).

Our aim is to help spouses, children, and other potential beneficiaries in BC learn how to navigate a will challenge – and when to seek legal help.

Understanding Will Contests in British Columbia

In British Columbia, certain family members have a legal right to challenge a will that they feel is unjust. BC law expects will-makers to make “adequate provision” for their spouse and children. If a will fails to do so, a court can step in and vary (change) the will to provide a fair share to the spouse or kids. This type of claim is unique to BC and is rooted in what used to be called the Wills Variation Act (now part of the Wills, Estates and Succession Act or WESA).

However, “contesting a will” can also mean challenging the validity of the will itself. Even if you’re not a spouse or child, you might dispute a will if you believe something is legally wrong with it – for example, if the will was made under undue influence or the will-maker lacked mental capacity. In short, there are two main categories of will contests in BC:

1. Fairness (Adequate Provision) Challenges: Only the spouse or children of the deceased can argue the will didn’t make adequate, fair provision for them. This is often referred to as a wills variation claim under WESA.

2. Validity Challenges: Anyone with a financial interest in the estate (such as a beneficiary or would-be heir if the will is invalid) can challenge the will’s validity on certain legal grounds (like lack of capacity or fraud). If a will is proven invalid, it gets thrown out and the estate would be distributed according to a prior valid will or, if none, under intestacy (as if there were no will).

Understanding which type of challenge applies to your situation is important, because who can contest and the grounds for contesting will depend on the type of challenge. Let’s break down who is eligible to contest a will in BC and on what grounds.

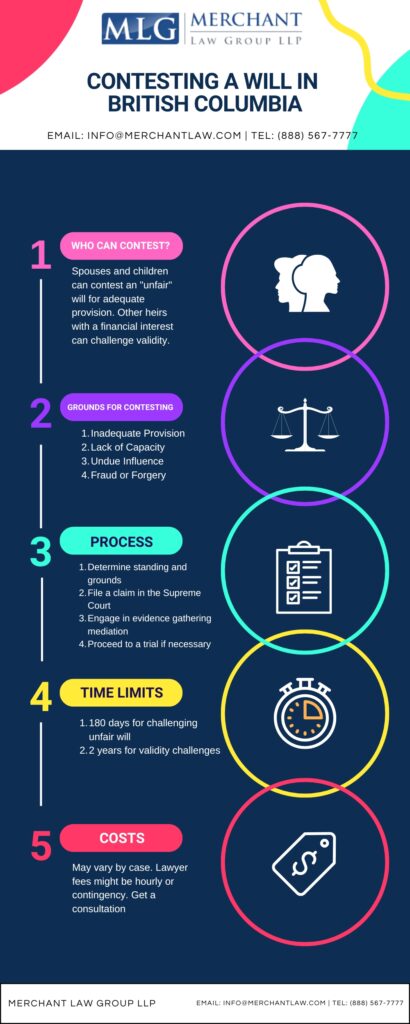

Who Can Contest a Will in BC?

Not just anyone can contest a will – you must have legal standing. In British Columbia, the WESA law is quite clear on eligibility:

1. Spouses and Children: Only a spouse or the children of the deceased can contest a will for being unfair or not providing enough for them. This includes common-law spouses (including same-sex or opposite-sex partners who lived in a marriage-like relationship for at least 2 years) and both biological and adopted children (including adult children).

For example, a married or common-law partner, or a son or daughter who was left out or given very little, can file a wills variation claim asking the court to rewrite the will to give them a proper share.

2. Others (e.g. siblings, grandchildren, other relatives): If you are not the spouse or child of the will-maker, you cannot make a claim simply because the will seems unfair to you – BC’s wills variation remedy is only for spouses and children. However, you might be able to contest the validity of the will if you have a legitimate interest. Typically, this means you were named in a previous will or would inherit under intestacy if the current will is tossed out.

For instance, a disinherited sibling or a family member may challenge the will by alleging it’s invalid (due to forgery, undue influence, etc.), but they must have solid grounds (we cover these next).

In summary, disinherited spouses and children are the primary challengers in BC for will contests based on fairness. Other potential beneficiaries (like relatives who would stand to inherit if the will was invalid) can only challenge a will on legal validity grounds. If you’re unsure whether you have standing, consider consulting a lawyer to confirm if you’re eligible to contest the will.

Grounds for Contesting a Will in BC

There are specific legal grounds on which you can contest a will. You cannot challenge a will simply because you feel it’s morally wrong or you expected something else – you need a recognized legal reason. Here are the common grounds to contest a will in British Columbia:

1. Inadequate Provision for Spouse or Child (Unfair Will): If you are a spouse or child of the deceased and the will did not “make adequate provision for your proper maintenance and support,” you can ask the court to vary the will. This is the wills variation ground under section 60 of WESA.

Essentially, you argue the will is unfair to you as a spouse/child. The court will consider factors like the size of the estate, your financial need, and the deceased’s moral obligations to you in deciding whether to re-allocate a portion of the estate to you.

Example: An adult son left out of his mother’s will could claim that, given the circumstances, the mother had a moral duty to provide something for him, and ask the court for a share.

2. Lack of Testamentary Capacity: A will can be contested if the will-maker (the person who made the will) was not mentally capable of understanding what they were doing when they signed the will.

To have testamentary capacity, a person must understand the nature of making a will, know what assets they have, and know who might expect to inherit. If the will-maker had advanced dementia, was heavily medicated, or otherwise impaired to the point they couldn’t comprehend those things, the will may be invalid.

Example: If an elderly parent with severe dementia signed a new will cutting out all children, the children might contest it by claiming the parent lacked capacity at that time.

3. Undue Influence or Coercion: If someone unduly pressured or manipulated the will-maker into making certain provisions, the will (or the affected part) can be challenged for undue influence. BC courts can invalidate any gift in a will that was made as a result of someone exerting force, fear, or extreme persuasion on the will-maker.

Example: A caregiver who threatens to stop caring for an elderly person unless they’re given a large inheritance could be found to have unduly influenced the will. A will made under such pressure is not truly the will-maker’s free intention

4. Fraud or Forgery: Although rare, if the will itself is a forgery or if the will-maker was deceived into signing a document not knowing it was a will (fraud), the will is invalid. For instance, if someone swapped pages or presented a document for signature under false pretenses, that would be grounds to nullify the will. Evidence of fraud will be needed, and these cases can be complex.

5. Improper Execution or Formalities: Wills are supposed to meet certain signing and witnessing requirements (in BC, usually signed by the will-maker in front of two witnesses who also sign). If the will was not properly signed or witnessed, it could be contested.

However, note that under WESA, the court can sometimes “cure” a will that doesn’t strictly meet formalities if there’s clear evidence that it reflects the deceased’s intentions. Still, obvious errors (like a missing signature) can give rise to a challenge.

Example: If a will had only one witness signature, an interested party might challenge its validity because BC law generally requires two witnesses.

6. Lack of Knowledge or Approval: Related to capacity and fraud, this ground means the will-maker didn’t fully understand or approve the contents of the will. Perhaps they signed it by mistake, or there was a serious misunderstanding about what was in it. This is less common, but can be argued if, say, the will-maker was illiterate or the will was in a language they didn’t understand.

7. Ambiguous or Multiple Wills: If there are conflicting wills or very unclear terms, someone might contest which will is valid or how to interpret it. (In such cases, the court’s role is often to interpret rather than invalidate, but it can become a legal dispute requiring resolution.)

Keep in mind: simply thinking the will is “unfair” isn’t enough unless you are a spouse or child with a legal right to adequate provision. If you’re just unhappy as, say, a friend or sibling who received less than someone else, you must find one of the validity grounds above to mount a challenge.

Also, no-contest clauses (clauses in the will that threaten to disinherit someone completely if they challenge the will) are generally not enforceable in BC against a spouse or child who has a WESA variation claim, but they might deter other beneficiaries. Always get legal advice if you’re facing a no-contest clause scenario.

How to Contest a Will in BC (Step-by-Step)

Contest a will in BC by confirming legal standing and valid grounds, consulting an estate litigation lawyer, gathering evidence, and filing a Wills Variation Claim in the Supreme Court of British Columbia. Mediation may be required before proceeding to court.

Challenging a will is a legal process, so it’s wise to proceed carefully. Here’s a step-by-step guide on how to contest a will in British Columbia:

1. Determine Your Standing and Grounds: First, figure out if you have standing to contest the will and on what grounds. Are you a spouse or child who was left out or received less than what’s fair? Or are you another relative who suspects the will is invalid?

Pinpoint the reasons: e.g., “I am the son and I wasn’t adequately provided for” or “I believe the will isn’t valid because Mom was coerced.” This step is crucial because it shapes the rest of the process.

2. Consult an Estate Litigation Lawyer: It’s highly recommended to seek legal advice early. An experienced BC wills & estates lawyer can review the will, your relationship to the deceased, and any evidence of problems (like medical records if capacity is an issue, or suspicious circumstances if undue influence is alleged). They will confirm if you have a viable case and explain your chances of success.

Most lawyers will discuss fee options (hourly vs. contingency => some may take will contest cases on a contingency basis, meaning you pay legal fees only if you win/recover funds.

Tip: Many BC law firms offer an initial free consultation for estate disputes.

3. File a Notice of Dispute (if probate is not yet granted): If the person whose estate it is has died recently and the will is in the process of being probated (probate is the court process to validate the will and authorize the executor), you can file a Notice of Dispute with the probate registry to put the brakes on probate. This is sometimes also called a “Notice of Objection”.

Filing this notice prevents the court from issuing probate to the executor temporarily, which is important if you are contesting the validity of the will. Essentially, it signals that someone is going to challenge the will, and it stops assets from being distributed in the meantime. If probate has already been granted, don’t worry, you can still proceed, as explained in the next step.

4. Start a Court Action to Contest the Will: To formally contest the will, you need to commence legal proceedings in BC Supreme Court (estate disputes are handled in the BC Supreme Court). The procedure differs slightly based on the type of challenge:

- Wills Variation Claim (Fairness for Spouse/Child): You start by filing a Notice of Civil Claim (a lawsuit) in Supreme Court, within 180 days of probate being granted (more on this deadline below!). In this claim, you state that you are a spouse/child and that the will failed to make adequate provision for you, and you ask the court to vary the will.

The executor of the estate must be named as a defendant, and typically other beneficiaries are included as defendants as well (since they have an interest in the outcome). - Will Validity Challenge (e.g., Undue Influence or Lack of Capacity): You might start an action by Petition or a Notice of Civil Claim to revoke the grant of probate (if probate was issued) on the grounds that the will is invalid.

If probate hasn’t been issued yet (because you filed a Notice of Dispute), you essentially ask the court not to grant probate on the submitted will due to the problems you allege. In your court documents, you’ll outline the evidence of, say, lack of capacity or undue influence.

The executor (or intended executor) and the beneficiaries named in the will (and perhaps those who’d inherit if the will is struck down) would be respondents in the case.

In either scenario, once the court action is filed, it’s crucial to serve the documents on the necessary parties. For a wills variation case, WESA requires that the filed claim be served on the executor within 30 days after the 180-day deadline (i.e. by 210 days after probate), and also on the Public Guardian and Trustee if there are minor children or incapacitated beneficiaries.

In a validity challenge, you would also serve the executor and all those who have an interest (e.g., the beneficiaries named in the will, and possibly intestate heirs). This notifies everyone involved that the will is being challenged.

5. Evidence Gathering and Negotiation: After the legal action is launched, there’s a phase of information exchange and evidence gathering (called discovery). Both sides may produce documents – for example, medical records of the deceased, the lawyer’s notes when the will was signed, emails or letters that show the relationships, etc.

Witnesses might give statements or be examined about the circumstances of the will. During this period, it’s also very common to engage in settlement discussions or mediation. In fact, many will dispute cases in BC settle out of court through negotiation or a mediation process.

Mediation is often faster and cheaper than a trial, and it allows the parties to reach a mutually acceptable arrangement. For instance, an disinherited child and the other beneficiaries might agree on a compromise where the child receives a certain sum, avoiding the need for a judge to decide. Courts encourage settlement in estate disputes when possible.

6. Court Hearing or Trial: If you cannot reach a settlement, the case will proceed to a court hearing (sometimes a full trial). Contesting a will in court can take time – often the entire process might take 1 to 2 years from start to finish, depending on complexity.

At trial, a judge will review all the evidence and legal arguments. The judge can then make a ruling:

- In a wills variation (fairness) case, the judge might agree that the will was unfair and order a different distribution (e.g. give the spouse or child a larger share). Conversely, the judge might find the will was acceptable and leave it unchanged.

- In a validity challenge, the judge might decide the will is invalid (for example, due to undue influence or lack of capacity). If so, the will is effectively cancelled and the estate would then be distributed according to the last valid will before that, or under intestacy if no earlier will exists.

The judge could also uphold the will as valid if the challenge isn’t proven, allowing the executor to carry out the original terms. - Sometimes the judge can uphold part of a will and void another part. For example, if only one provision was influenced by fraud or undue influence, that part can be struck out without invalidating the entire will.

7. Finalizing the Estate Distribution: After the court’s decision, the executor (or a court-appointed administrator if the will was thrown out) will then distribute the estate according to the judgment. If the will was varied, the will’s terms are effectively changed and the assets are divided up as the court directed.

If the will was invalidated, distribution will follow the new plan (earlier will or intestacy rules). This final administration can take a little additional time, but at this point the major dispute is over.Throughout this process, staying within legal timelines and following the correct procedures is crucial.

Missing a deadline or a step can jeopardize your case, so having a lawyer guide you is extremely valuable. Next, we’ll go over the time limits in more detail, since they are so important in BC will contests.

Time Limits: How Long Do You Have to Contest a Will in BC?

Timing is critical when considering a will challenge. British Columbia has strict deadlines for contesting a will, especially for spouses and children bringing a variation claim:

1. 180 Days from Probate – Wills Variation Claims: A spouse or child seeking to vary a will for inadequate provision must start the court action within 180 days from the date the court issues the grant of probate.

In other words, once the will has been officially probated, the clock starts ticking on a roughly six-month window to file your claim.

If you miss this 180-day deadline, you likely lose your right to make a WESA variation claim. (There are very limited exceptions – for instance, if you genuinely didn’t know about the will or probate in time, the court might extend, but don’t count on it without very good reasons.

2. 30 Days to Serve Executor (up to 210 Days Total): After you file the claim, BC law also requires that you serve the claim on the executor within 30 days after the 180-day period ends. Effectively, this means by day 210 after probate.

During this 180-210 day period, the estate is typically on hold. In fact, the executor is not allowed to distribute the estate to beneficiaries during the first 210 days after probate (unless all interested parties consent or a court orders otherwise.

This waiting period built into WESA is specifically to give time for any will contests to be brought forward.

3. Will Validity Challenges – Ideally Before Probate, or Within Limitation Period: If you are challenging the validity of the will (not a spouse/child fairness claim, but issues like capacity or undue influence), there isn’t a special 180-day rule, but general limitation periods apply.

It’s best to file a Notice of Dispute before probate is granted to pause things.

However, if probate has already been granted, you can still launch a challenge. Typically, there is a 2-year limitation period in BC for civil claims (under the general Limitation Act) counting from the date you knew or ought to have known of the grounds for challenge.

For example, if you discover a year after probate that there was possible fraud, you likely still have up to 2 years from discovery to start a claim to revoke probate. That said, acting sooner is better, because if the estate has been distributed by the time you act, it becomes much harder to recover assets.

In summary, spouses and kids have 180 days post-probate to initiate a will variation lawsuit. Others with validity challenges should ideally act before probate (via a notice of dispute) or as soon as possible, usually within two years at most. Don’t delay if you believe you have a claim. If you’re approaching a deadline, talk to a lawyer immediately. Missing the window can mean losing your chance to contest the will forever.

Average Cost to Contest a Will in BC

One of the biggest concerns for anyone considering legal action is, what will it cost? The average cost to contest a will in BC can vary greatly depending on the complexity of the case. There isn’t a one-size-fits-all price tag, but here are some key points on costs:

1. Legal Fees Can Be Significant: Contesting a will often requires many hours of a lawyer’s time → investigating facts, gathering evidence, filing court documents, attending hearings or mediation, etc.

If the dispute settles early, costs might be relatively moderate. But if it proceeds to a full trial, it can easily cost tens of thousands of dollars in legal fees. In a complex estate fight, fees can even reach the high tens of thousands or more, especially if the trial is lengthy. Because of this, it’s important to weigh the potential benefit (what you might gain from the estate) against the cost.

For example, it may not make financial sense to spend $50,000 litigating if your expected inheritance is $20,000.

2. Hourly vs. Contingency Fee Arrangements: Estate litigation lawyers may charge by the hour (common rates might be anywhere from $250 to $500+ per hour depending on experience and region). Some firms might agree to a contingency fee for will contest cases.

A contingency fee means you do not pay upfront legal fees; instead, the lawyer gets a percentage of whatever amount is won or settled. This can be helpful if you can’t afford to pay out of pocket.

However, not all cases or lawyers qualify for contingency. It often depends on the strength of the case and the size of the estate.

Tip: Ask in your initial consultation about fee options. Our firm Merchant Law Group LLP gives clients a choice of hourly or contingency in certain cases.

3. Court Costs and Disbursements: Aside from lawyer fees, there are other expenses (called disbursements) such as court filing fees, process server fees to serve documents, costs for expert reports (for example, a medical expert’s opinion on capacity), and mediation fees if you go to mediation. These can add a few thousand dollars or more, again depending on the case.

4. Who Pays If You Win or Lose: The outcome of the case can affect who ultimately pays the legal costs. In BC, as in most of Canada, the general rule is that the losing party usually pays a portion of the winning party’s legal costs (this is called “costs” in the court’s judgment).

If you win your will challenge, the court may order that the estate or the other side cover some or all of your legal bills. If you lose, you might be on the hook not only for your own legal fees but also some of the other side’s costs.

However, in estate cases, judges have discretion. Sometimes, if the case raised a genuine question (like a real concern about the will’s validity), the court might order costs to be paid out of the estate rather than penalizing the loser.

For example, courts have allowed estate funds to cover costs when a will’s meaning or validity was in serious doubt and it was reasonable to have the issue decided.

Bottom line: you should be prepared for the possibility that if your challenge isn’t successful, you could have to pay significant costs.

5. Initial Consultation – Usually Free: On a positive note, many estate litigation lawyers in BC offer a free initial consultation. This means you can often get an initial opinion at no cost, which can help you decide if it’s worth pursuing. Always verify any fees upfront when engaging a lawyer.

Remember: Every case is different. The cost will depend on factors like how complicated the estate is, how many parties are involved, whether it settles early or goes to trial, and the billing arrangement you have. Don’t be afraid to discuss cost expectations and strategies with your lawyer (for example, whether to try mediation early to save money).

While contesting a will can be expensive, a strong case involving a sizable estate can be worth it, especially if you stand to gain a much larger inheritance that was improperly denied to you.

BC’s Wills Variation Act (WESA) – The Law Behind Fair Inheritance

You’ll often hear about the Wills Variation Act in discussions of contesting wills in BC. This was the old law (dating back decades) that allowed spouses and children to challenge unfair wills.

In 2014, the Wills Variation Act was incorporated into the new Wills, Estates and Succession Act (WESA), which is now the governing law.

Section 60 of WESA is essentially the wills variation provision, and it states that if a will does not make adequate provision for the will-maker’s spouse or children, the court may order a provision that it thinks is adequate, just and equitable out of the estate for them.

In practice, what this means is that in BC a will is not absolute when it comes to spouses and children. The law recognizes a moral and legal obligation to family. If a parent or spouse in their will leaves a spouse or child with an unfairly small share (or nothing at all), the court can step in to reallocate the estate.

WESA sets out the rules and timelines (like the 180-day deadline) for these claims. When we use the term “Wills Variation Act”, we’re referring to this family provision part of the law.

If you are a spouse or child considering a will contest in BC, your case will likely be a WESA wills variation case (unless you are also claiming the will is invalid for other reasons). The legal basis for your claim is this section of WESA that protects spouses and children from disinheritance.

You do not need to quote the law in your claim, but it’s empowering to know that BC has this protective law on the books. You’re not asking for a “handout,” you’re invoking a legal right created by the BC legislature to ensure fairness in wills.

For those who are not spouses or children, WESA also contains many of the rules about will validity (execution, capacity, etc.) and the probate process.

So either way, WESA is the key statute. But the headline is: the “Wills Variation Act” lives on inside WESA, giving spouses and children in BC a unique ability to contest a will that other jurisdictions might not allow.

Getting Help – Talk to a Lawyer

Contesting a will in BC involves nuanced law and strict procedures, but you don’t have to navigate it alone. It’s a good idea to get professional guidance before you embark on a will challenge.

An experienced BC estate litigation lawyer can assess your situation and help you decide your best course of action. They will know how to gather the right evidence (for example, medical records or witness statements), how to file the necessary court documents on time, and how to negotiate with the other side to achieve a fair settlement if possible.

Merchant Law Group has knowledgeable wills and estates lawyers serving clients across British Columbia. If you’re considering challenging a will – whether you’re a disinherited spouse or child, or you suspect a loved one’s will is invalid, our team can help you understand your options.

We offer compassionate, client-focused service with a deep understanding of BC’s WESA (Wills, Estates and Succession Act) and the former Wills Variation Act.

Contact Merchant Law today for a free consultation to discuss the prospects of your case. We can guide you through each step, from filing objections to representing you in court, working hard to protect your rights and ensure you receive what you’re entitled to under the law.

FAQ: Contesting a Will in BC – Common Questions

Q: Do I need a lawyer to contest a will, or can I do it myself?

Technically, you are allowed to represent yourself in court. However, contesting a will is a complex area of law with strict deadlines and procedural rules. It involves interpreting legal statutes (like WESA), possibly obtaining expert evidence (like medical opinions on capacity), and making legal arguments.

Any mistakes in process (for example, missing the 180-day filing deadline or failing to serve the right parties) could derail your case. Because the stakes are usually high (important family relationships and significant assets). It’s highly recommended to hire a lawyer who specializes in estate litigation.

An experienced lawyer will know how to build the strongest case for you and improve your chances of success. Given that many offer an initial free consultation, it’s worth at least speaking to a lawyer to understand what’s involved before attempting anything on your own.